“Still, why not have the benefit of being thought disagreeable – the luxury of recorded observation?”

– Henry James, The Impressions of a Cousin.

In late January, the Center for Jewish History hosted a panel of information professionals on the topic of WikiLeaks. I paid the $10 entrance fee and sat in the audience. Scantly did I know other folks at the gathering, and sat alone, having just got off work and still in that unrelieved decompression zone that barnacles one who works a job that you above all do not bring home with you. When I walk out of the Croisic Building on 26th & Fifth Ave it is like the Biohazard agent returning from the Danger Zone in his Hazmat suit to the de-radiation chamber before entering the secret control room where tired analysts eat Fritos. The security at the WikiLeaks event must have been on to my trip, since I was probed twice going in before they found the loose coinage I didn’t know was in the pocket of my London Fog.

The combined pedigrees of the five panelists, as read off by moderator Peter Wosh, of NYU, spanned a swooning horizon of opportunity for a student hoping to make a living in the Archives field. A magnum of verbiage which one might paste to one’s name, for sustenance. The litany of pedigrees cast the panelists in an almost intimidating light as they sat on stage in grouped silence, like bishops of the Church. But by the end of the event, after all bishops had spoken, the spell drooped. Like the classroom, some were well-spoken, and others a tax on the good intention of good attention.

When provoked, the panel did not bite, and did not want to bend either way to the topic at hand. Ms. Trudy Huskamp Peterson, an ex-Archivist of the U.S., was smart and informative and broke down some of the bullet points behind the way WikiLeaks functions. But when it came to the big issues – spying, law enforcement, lack of security – she was mum (the panel aside, Ms. Peterson responded to an inquiry I posted on the SAA listserve with an abundance of archival tips for which I was eagerly and bowingly grateful). Mr. Pulzello, a “Solutions Architect,” struck one as probably not the consultant most capital for hire, the type who takes 20 mins to answer a question that could have been answered in 2, like an uncle who talks about cars all the time while sitting in his armchair. An audience member asked a question about the accountability one might find themselves beholden to after a grave breach of security. The Solutions Architect, with the hunched air of a glib moral stickler, advised the woman that she should prepare her resume for a new job. She must have had a sense of humor, because she didn’t laugh.

One should not exactly expect William F. Buckley v. Gore Vidal at an Archivist panel, but there is no shortage of potential agitation regarding the topic of WikiLeaks. It was as if whale oil merchants had gathered at town hall to discuss the advent of gas light. I had an existential moment wondering what we were all doing in the audience, staring up at these talking heads, like what happens when you go to a bad movie you thought would be good. Maybe I was the moral stickler.

One should not exactly expect William F. Buckley v. Gore Vidal at an Archivist panel, but there is no shortage of potential agitation regarding the topic of WikiLeaks. It was as if whale oil merchants had gathered at town hall to discuss the advent of gas light. I had an existential moment wondering what we were all doing in the audience, staring up at these talking heads, like what happens when you go to a bad movie you thought would be good. Maybe I was the moral stickler.

The most lively and interesting of the group, a CUNY professor who blogs on information law, concluded with the ironical prospect of “doing nothing” in response to WikiLeaks – the idea that attention-hogs are best disarmed by ignoring them. He had a lively schpiel, the most performing of the group, but when this idea was challenged by an audience member, the panel responded with silence, as if exercising the Fifth Amendment at a mob trial.

It would have been encouraging to hear someone at least stick up for Julian Assange. Whether from personal belief or the risk of peer alienation, no one did. There were phrases dropped by the panel which I did enjoy, like “stovepipe of information,” and “costless storage,” and “netcentric diplomacy,” which it would seem Julian Assange is a champion of, though no nod was made by the speakers. As a greenhorn, just a student and intern, and a new audience member to esteemed panels, I ventured to assume that such tiptoeing must be how one gets invited to esteemed panels. In all, it was encouraging to have WikiLeaks caucused by the Archives world. I chose to skip the post-panel reception, where I might have, along with wine and cheese, stuffed my maw with the proverbial foot and discouraged any prospect that foot might have of crossing paths in the future with anyone in attendance. The point is to have a job you don’t have to scrub-off at the end of the day.

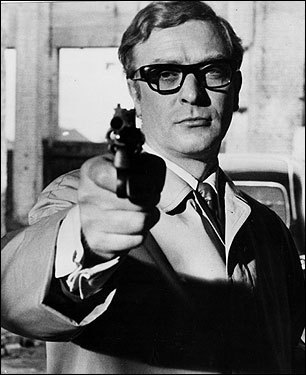

The information materials with which Julian Assange barters – the classified cables, videos, documents, etc. – are not “his,” in that he had nothing to do with their generation or recordsmaking, yet Assange has roguishly granted himself the authority to broker deals with the Fourth Estate using these materials as currency. In a recent New York Times Magazine cover story, editor-in-chief Bill Keller synopsizes the paper’s coterminous relationship with WikiLeaks as if the secrets had not been already planned to be made public on WikiLeaks. Keller may underestimate the capabilities of the average reader to digest information. The Times, like Der Spiegel and the Guardian, saddling themselves with a certain responsibility to protect both the public and government, acted as press agents for Assange. They helped Assange sell tickets to the show. Like the Wiki-panel, Keller treats Assange offhandedly while at the same time indulging the journalistic intrigue which Assange prompted for the newspaper. These major newspapers enter into Assange’s black market, and then capitalize on the lawlessness in order to dishonor the agreements previously made, in the style of 1960s spy movies.

Like Bill Keller at the Times, Assange is listed on the WikiLeaks masthead as its “editor-in-chief.” The Times, in its coverage of the release, refers to the collection as an “archive.” Julian Assange is a unique kind of paranoid archivist, and the controversy caused by WikiLeaks portends a society where no power controls information. Assange avows that WikiLeaks is a work of “scientific journalism,” which “allows you to read a news story, then to click online to see the original document it is based on. That way you can judge for yourself: Is the story true?”

The open media sources which exemplify the creed of WikiLeaks distrust the analog filters of media and the law. Politicians have employed the semantic tropes of Populist agitation against Julian Assange. His actions have been equated with terrorism, and enforcement of the Espionage Act against WikiLeaks has been bandied about in the press. Some have even called for Assange’s assassination. Such Sunday morning talk-show vigilantism casts Assange as both a crusader and an agitator, and serves the behavioral patterns of Populism in the United States. But where Populists after the Civil War drew meagerly from the words of the small town press and travelling speechmakers, the political critics of WikiLeaks fear that the digital data stream is drowning society in information.

The outcry against Assange has been voiced by both the Right and Left, insofar as such bicameral ideologies make habit of afflicting their own platforms. Politicians aligned with the 21st century, in-vogue monkeywrench reactionary Tea Party have voiced a pick-axed opposition to WikiLeaks, as has Democratic Senator of California Dianne Feinstein, who deliberately used the op-ed page of The Wall Street Journal to invoke the Espionage Act against Assange, recalling that the Act is founded on the idea that information can indeed cause injury to the U.S. Government.

By releasing classified State Department cables, which involve the diplomacy of world nations, WikiLeaks frames the United States as a formidable archival central command. If an archive can be defined as a set of materials which has outlived its primary use, then the fact that the New York Times refers to a collection of WikiLeaks documents as the “Iraq War Archive” might suggest to readers that the war is over. For Julian Assange, the secrecy promotes the meaning and gravity of the files, and the context of history loses meaning without the conspiracy that history is presumed to be.

In 1890, Ignatius Donnelly, a Minnesota Congressman, published a novel of pseudo-historical science fiction, Caesar’s Column, to promote his vision of a future doomed by the sickness of the present. Set in 1988, “rapacious business methods, the bribery of voters, the exploitation of workers and farmers by the plutocracy” bring about “a sadistic anti-utopia” whose capital is New York City, where the high bright lights disregard the old dichotomy of day or night.

The future of Ignatius Donnelly is no less cataclysmic than the intentions behind the hackers’ consortia which threaten to demobilize the corporate data-wave in defense of WikiLeaks. An online aggregate of e-protester anti-communities under the name “Anonymous” had indicated the vulnerabilities it is ready to exploit in the digital infrastructure of MasterCard and PayPal. Not unlike the Sedition Laws of the young United States, such cyber-sabotage asserts itself in support of the freedom of information. In turn, Apple Inc., an arkheion of technological lifestyle, subsequently dropped the WikiLeaks application from its iPhone, citing that it “violated our developer guidelines.” Each maneuver between those in favor of and those against WikiLeaks results in the withholding of info.

“Democratic societies need a strong media,” Assange argues, because “the media helps keep government honest.” After Assange’s release from police custody in London, a result of sex crime charges, Judge Riddle ordered that Assange must reside, under surveillance, at Ellingham Hall, a Georgian mansion owned by Vaughan Smith, the founder of The Frontline Club, a society of journalists. Perhaps the Judge intended to punish Assange by imprisoning him in a domicile of newspeople.

“Democratic societies need a strong media,” Assange argues, because “the media helps keep government honest.” After Assange’s release from police custody in London, a result of sex crime charges, Judge Riddle ordered that Assange must reside, under surveillance, at Ellingham Hall, a Georgian mansion owned by Vaughan Smith, the founder of The Frontline Club, a society of journalists. Perhaps the Judge intended to punish Assange by imprisoning him in a domicile of newspeople.

There has been plenty of blowback against Assange, which he surely must have expected, and indeed might relish. In this context, the “do nothing” policy offered at the Wiki-panel might serve the purpose of transcending revenge paradigms. Assange’s alleged profile on OK Cupid, the hook-up website, has been leaked, as well as a continuum of legal documents regarding his rape investigation.

Meanwhile, Assange is not the true whistleblower. The documents posted on WikiLeaks were retrieved by Private First Class Bradley Manning (downloaded to CDs marked “Lady Gaga,” which serves the patterns of pop culture and secret information exemplified by the Watergate scandal voiced by “Deep Throat”). Bradley Manning now languishes under 23-hour solitary confinement in a military prison, while Assange drinks tea and decks himself in British-spun raiment. News coverage of Manning’s incarceration indicates that the case against the PFC is foundering. A detailed breakdown of how Manning was able to access the secret documents is described here by the National Journal – essentially an indirect result of mismanaged intelligence overhauling by the U.S. government after 9/11.

The lifestyle of technology excites the hope that information is subject to its users rather than the users subject to it. The U.S. government has retorted that the information in the WikiLeaks documents itself is not of gravest consequence, but that the act of defying classified status is an act of espionage. The file means nothing without the technology by which it is coded. Populists fabricated the evidences of knowledge in fantastic novels and town square hamhock oratory. WikiLeaks bases its actions on the open record, kept secret less because of security, than because of power. The consequence is history.